Can a True Martini be a Martini without Vermouth?

|

|

Time to read 8 min

|

|

Time to read 8 min

A little while back my wife Karen and I were contemplating dinner in the Airbnb apartment we had rented in the Italian (more or less) city of Trieste, which is perched on the northeastern corner of the Adriatic Sea in such a way that it gazes on the rest of the country across an insulating, calming stretch of water.

We’d been dining out for too many days in a row (poor us!) and all we wanted was a quiet night in with a simple dish of pasta and perhaps an old Hollywood classic dubbed into Italian on TV. In any other Italian city, we would have already had our fill of simple dishes of pasta, but Trieste is as much Austrian and Slovenian as it is Italian, and you’re as likely to get dumplings—airy little potato ones or big, knobby bread ones—in goulash or palacinke (crêpes) in basil butter as you are penne in tomato sauce.

But before we could make the pasta there was the question of the Aperitivo, an essential part of any balanced dinner. Now, Trieste has at least one top-notch old cocktail bar, the Antico Caffè Torinese, where Massimo or Matteo can and will twist you up any old classic your liver desires. But in general, the locals devote the pre-dinner hour to Aperol or Hugo Spritzes (the “Oogo,” as it’s pronounced, is the drink of Italy’s northern mountains, made from prosecco, elderflower syrup and soda, with a sprig of mint). If they’re not drinking those, they’re drinking birre medie alla spina—draft Beers, size medium. All fine things, but after a week plus in town, Karen’s and my Martini counts were perilously low. Fortunately, we had half a bottle of Plymouth Gin leftover from the night we had Southsides made with the lovely local mint. What we didn’t have was dry Vermouth.

In Italy, you can buy a bottle of liquor just about everywhere. Candy stores, tobacconists, cafés, supermarkets, bakeries, butchers, greengrocers, ice cream parlors, superettes, cheesemongers, souvenir shops and so forth are all allowed to compete with full-fledged wine and Spirits merchants in selling booze in the bottle, and just about all do, in a small way. That’s the good news. The bad news, and it’s not that bad, is that this means that while you’re surrounded with places to pick up a bottle of Campari, domestic Vermouth, or the local Amaro (in Trieste, that’s Pelinkovac, a sort of Balkan Absinthe), if you want something even slightly unusual you’re going to have to find one of the few true Wine and Spirits merchants.

Dry French Vermouth being one of those slightly unusual products, it wasn’t looking good for our Martini levels. I’ve never liked using the Italian version of dry Vermouth in a Martini and after walking all day the idea of trudging the eight or ten blocks to the good liquor store was a non-starter. But as I was peering into the refrigerator in the hope that a half-bottle of Noilly Prat would somehow materialize there, my eye caught on the remains of a bottle of white Wine in the door and I thought of Giuseppe Cipiriani.

Cipriani, one of the twentieth century’s great barkeepers, founded Harry’s Bar in Venice in 1931. Nowadays, Harry’s is part of a vast commercial empire controlled by his descendants (Cipriani died in 1980) and is distinguished largely by the impossibly high prices it charges and the brutal stiffness of its Martinis, which are served in the so-called “direct” style (where the Gin and Vermouth are kept in the freezer and combined without stirring with ice to avoid any dilution), premixed to Ernest Hemingway’s “Montgomery” proportions: 15 parts Gin to one part Vermouth.

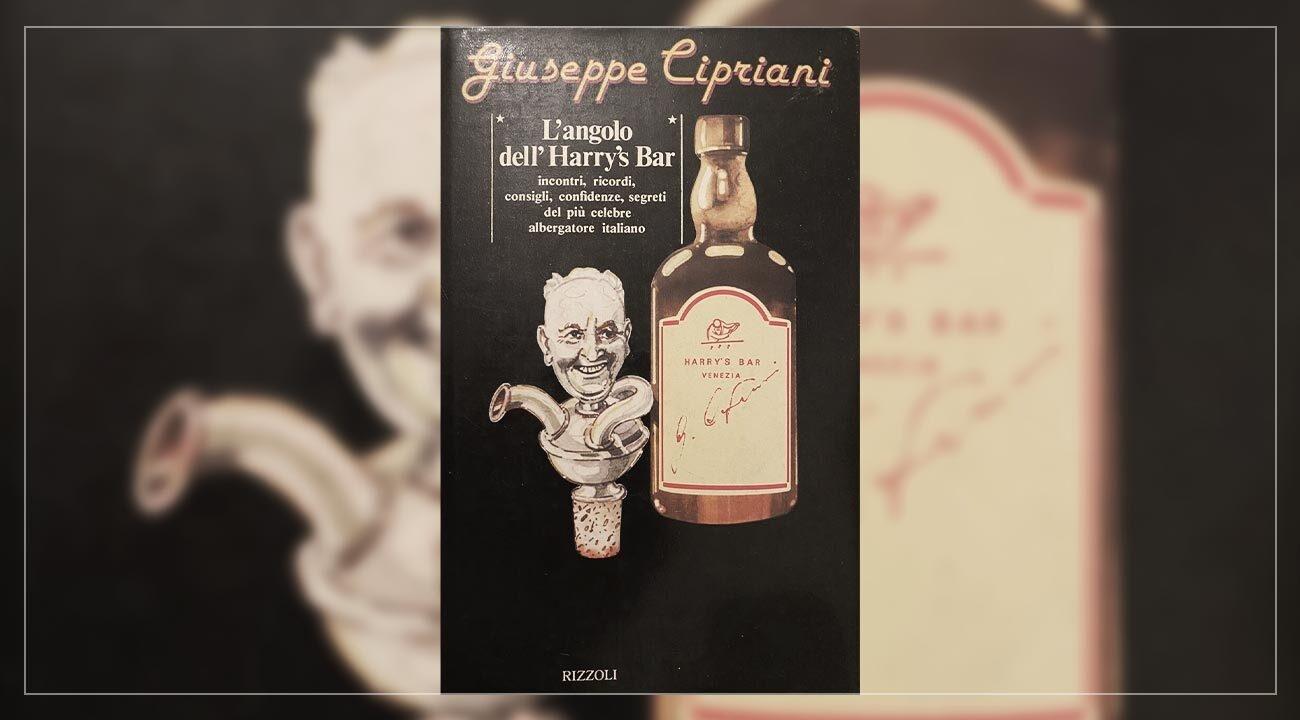

But that’s now. In 1978, Giuseppe Cipriani published L’angolo dell’ Harry’s Bar (that is, The Corner of Harry’s Bar), a witty, informal memoir that should be one of the foundational texts of a master bartender’s education. In it, he mostly talks about hospitality, something few modern bartenders’ guides bother with. But there’s also a little bit of theory of mixing drinks, and in particular, the Martini, which he writes, “is good when it is dry, not watery, served in the proper measure and in a glass adapted to it.”

A Martini is good when it is dry, not watery, served in the proper measure and in a glass adapted to it.

By dry and not watery, however, he does not mean the Hemingway-Montgomery Martini: in fact, he specifically includes Hemingway’s formula as an “eccentricity;” one of the “pretty strange requests” that customers have sometimes faced him with. A proper barman, he implies, must have the good sense to indulge a customer perverse enough to order such a thing without letting it influence him otherwise or deflect him from the proper path.

Only at the end of the book does Cipriani give his own Martini recipe, or at least one of them. Like the one you get at his bar today, it is meant to be premixed and kept in the freezer, and it consists of two ingredients. But there the resemblance ends. For one thing, its ingredients are kept in the refrigerator, not the freezer. This means that when they are combined and stirred with ice, as Cipriani directs (another major difference), there will be some dilution. Not as much as if they were stored at room temperature, to be sure, but still enough to soften the drink and blend its flavors.

The differences don’t end there: for his proportions, Cipriani goes with a relatively gentle four to one, not 15 to one. And finally, he does not use Vermouth at all: instead, he specifies “Vino Tocai.” This Tocai would not be the famous Hungarian Tokay, but rather the Wine made in the hills and valleys between Trieste and Venice from the grape formerly known as “Tocai friulano” (AKA Sauvignonasse or Sauvignon vert). This “Friulano,” as it’s simply known now (the Hungarians complained about the “Tocai” to the EU a few years back) yields a very dry, mineral white whose fragrance is a little melony, a little almondy, and not particularly floral.

No matter. When I first read Cipriani’s recipe, I found it unusual—even downright odd—enough for it to lodge itself in my memory, proportions, procedure and all. Not that I was going to try it: I mean, a Martini with no Vermouth is not a Martini, right? This was simply another example of people who should know better striking out in a new direction and promptly getting in over their skis. I mean, Giuseppe Cipriani might have invented the Bellini and Carpaccio, but what did he really know about the Martini? White Wine. As if.

You can see where this is going. The quarter-bottle of white Wine we had left in the refrigerator was of course Friulano, we had enough Gin and ice and even a lemon for twists, and we were on vacation, so what the hell. Tough times make monkeys eat red peppers, as the old mob boss Frank Costello used to say. It took just a moment to put a pair of white Wine glasses in the freezer to chill, open a bag of potato chips (an essential accompaniment to any Italian Aperitivo) and stir up a pair of Original Harry’s Bar Martinis. Which were—inevitably—delicious. When you mix a little Tocai friulano with Gin it fades right into the background, supporting the Gin’s aromatics and adding to its texture without competing with it. The result is one of the most elegant of Martinis: cold, crisp, and clean, with hints of hidden depths but no vulgar display of botanical exuberance.

I’ve been writing about Martinis since 1999 and mixing them since, I dunno, 1982. If you’ve been doing something for a very long time, it’s easy to rely so much on your experience that you can’t picture another way of doing things possibly working, even if it comes recommended by people with impeccable credentials; by people like Giuseppe Cipriani. It’s good to get jolted out of that certainty from time to time, particularly if the thing that does the jolting is icy and delicious and comes with potato chips.

Note on Ingredients:

The biggest issue here is the Friulano Wine. In Trieste, it costs around €5.00 a bottle and can be bought just about anywhere. In America, alas, it’s peskily hard to find and expensive when you do. The regions you want to look for are Friuli, Colli Orientali del Friuli, and Collio, but even if you can find those, most of the whites exported here are made from other varietals. You may just have to experiment. What you want is something crisp and not too aromatic, with a lot of minerality and a medium level of acidity. I’d start with a Sauvignon blanc.

For the Gin, you want something not too strong, lightly aromatic and balanced. Plymouth is my Gin of choice here, but Beefeater also works very well.

Cipriani’s procedure is quite simple.

Since wine goes off quickly, I prefer to get the most out of my hard-to-find Friulano by mixing these by the bottle. This can live in the freezer, ready for use whenever you need it, and it’s even simpler than the single version. Here’s how.

This will need to be prepared at least two hours in advance. Since Cipriani’s original technique of stirring the chilled ingredients with ice adds another 20 percent water (I measured); for a bottle prepared well in advance, there’s no need to stir and strain; you can simply add the water. Combine the Gin, wine and water into a clean 750-ml screw-top bottle, agitate it briefly and stick it in the freezer along with your glassware. To serve, pour 2.5 to 3 ounces into a chilled glass and twist lemon peel over the top. The bottle will hold at least eight Martinis. Plus you’ll still have five glasses of Wine left over to go with your sardoni impanai—butterflied, breaded and fried sardines, a Triestino specialty.